Senior Year — Winter Quarter 1968

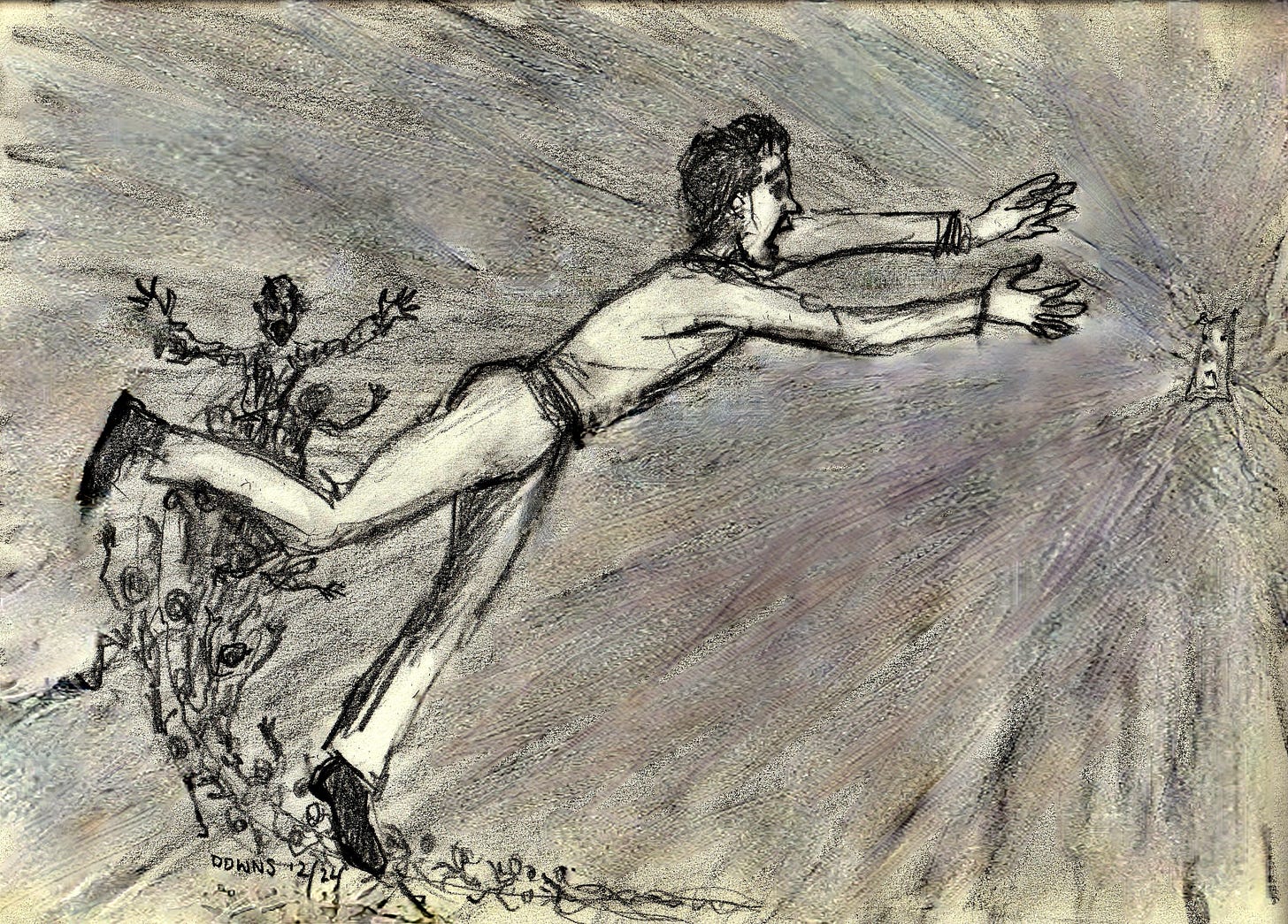

I’ve been keeping Jerry out of my life, but I feel energies gathering like the super-slow-motion collision of continental plates. And some days I’m like Disney’s Alice, running to keep ahead of the people chasing her, swimming in the emptiness toward the living doorknob that offers hope of escape. For her it’s a dream and she will wake to falling leaves fluttering in her face. For me, it’s reality. I won’t wake from this.

Whenever I go to the house, I tell myself I don’t care if Jerry’s there. But if he isn’t there, I don’t stay. Tonight, the house is quiet. I find Tom Graize listening to The Stones in the upstairs study room. He and Huna didn’t get the apartment beneath Bronko and Jerry and he lives in the house. He looks up when he sees me and is almost glad.

“Downs, let’s get out of here and go to Teddy’s for a brew.”

He’s lean, an inch taller than me, with craggy cheekbones and acne scars that deep crease his face when he smiles. In his ROTC uniform, he could be the soldier in the armed forces poster. We’ve pretty much avoided each other for four years. He must need company tonight as much as I do.

Teddy’s is crowded and is always loud. They pour draft beer in “fishbowls” that look like big glass chalices. Drink of this.

We find a small raised table with two high stools. We stick to safe topics: classes, ROTC, the modified pledge program.

“Last night brother Ross told pledge Mallet to drop for fifteen,” I say, “and pledge Mallet said, ‘Eat shit, sir’ and brother Ross laughed and said, ‘How about ten?’ and pledge Mallet said, ‘Fuck off, sir’ and they laughed.”

Graize sits up a little straighter. “I miss the bullshit intimidation and assholic humiliation by which a pledge learned to value becoming a Brother in the Bond,” he says and he smiles, the left side of his mouth pulling down as if it’s resisting the laugh. “Good thing I don’t give a fuck anymore.”

“Yeah, even Huna didn’t come to the last happy hour.”

“Huna blows dead dogs.” He lifts his fish bowl and drinks big swallows, looks past me and out the window. “He’s pussy-whipped.”

“How long have he and Sandy been pinned?” Not that I care.

“Too fucking long.” A lop-sided laugh. “Coupla weeks.” He leans back. “No time for Crow Row anymore.” It was some time freshman year that Tom got pinned and it was when they were depinned last year that he became one of the Crow Row drinking regulars. I watch him stew a little. “And fucking Rag and Bronko are acting like Conrad fucking Hilton about using their fucking apartment.” He drinks. “I think Cathy Armer finally dumped Rag.” He’s enjoying venting a little and I don’t think he’s all that serious.

I look to the doorway as Jerry comes in.

“Hey,” he says, “nobody told me there was a Teddy’s Train.”

Graize brightens. He jags around on the surface of things for a few minutes and then he leaves. “Paper due tomorrow.” He’s glad to be able to go.

We watch him pass outside the window.

“Seismic rumblings at Crow Row,” I say. “Graize said Huna and Sandy got pinned.”

“Yeah.”

Each of us puts his hands around his fishbowl and looks in it as if the answer to why we are awkward with each other can be found there.

“And it’s looking like Bronko and Cookie have about had it,” he says.

We talk about classes. I tell him for the last couple of weeks I’ve felt closer than ever to a nervous breakdown. It’s true, but I’m telling him so that he’ll feel better about whatever it is he’s feeling. Or something. “And I’m trying to write my comp. Gotta get something major to Kerder next week.”

“Yeah, I’ve been wondering why I thought an 8:00 a.m. astronomy class would be a good idea.”

Another silence.

“I meant to come to your place,” he says, not looking at me. “Make the first move.” He waits for me to jump in and tell him everything’s fine. I don’t. “But I just never got around to it.”

“No need for first moves.” I’m quiet, conversational. “Anyway, I don’t need to hear about your noble intentions.”

My words surprise both of us, but the energy is weariness not aggression. Maybe that’s worse. “Best just to leave well enough the hell alone, okay?”

We talk for a few minutes and then we walk up the hill together, mostly in a silence shared and not antagonistic. Maybe sad.

I spend hours at a time trying to write the goddamn comp and most of the time I tear everything up anyway. Kerder creams over the one story I think sounds like everybody else. What it’s about is obvious. How it gets there is obvious. But Kerder loves it, wants me to keep working on it because it could be really good. “Not just really undergraduate good, but really good.” I enter it in the Sarah Homer essay contest.

It takes about twenty consecutive hours of typing to finish the comp. There are lots of pages where the typing goes past the red margins. And is there a limit to how many smeared erasures a comp can have? I get it to Kerder’s office about twenty minutes before the deadline. He isn’t there and I’m glad; I slide it under his door.

On the way back to crash at the apartment, I go to the Grill and find Lynn Garner and Bill Barnes and John Watson, the president of S. E. T.

“Lynn, please don’t hate me, but is there some way you can get someone else instead of me to do one or two of the scenes for your comp?”

They all laugh.

“What?”

“I was just telling Bill and John,” Lynn says, “that Mrs. Bard wants me to get a different boy for each scene so I don’t share the performance with only one person.”

Bill’s smiling. “And she was hoping it wouldn’t hurt your feelings.”

The days are coming at me like the cards come at Alice, but some days there’s just enough updraft to keep a guy aloft and the cards only fluttering in the wind.

*****

It’s Friday night. Late. Almost closing time at the Pizza Villa. In the kitchen beyond the service window, Mama Rose’s twin daughters are working. They’re as blonde and blue-eyed as Mama Rose is dyed black and dark-eyed. They’re as cute and vivacious as Mama Rose is homely and vulgar. I look for signs of their rumored willingness to engage with the Allegheny men, but what would I know about it? They seem friendly and bubbly as teenage waitresses should.

“You okay?” It’s Mama Rose behind me. She comes to the other side of the table and sits across from me. Is this the first time she’s done that? There are only a couple of others in the place. Sigs at the front table. “You don’t come around as much as you used to. You seem lonely.” Her face assumes a concerned expression I’ve never seen on her. And her eyes without mischief or provocation seem lusterless, blank.

I’m trying to think of something to say that doesn’t sound clever. “Some days you get the bear,” I say and her eyes spark as she smiles and says, “And some days you gotta kick the bear in the balls before he gets you.”

I laugh more in surprise than humor. “Yeah, well.” I have nothing to say.

“Sometimes you need to get rid of your problems even when you can’t.”

I think I look puzzled.

“Like when you wake up with a piss hard on so bad you can’t piss,” she says and she leans in a bit just as one of her daughters rings the bell on the counter and says, “Mushrooms, pepperoni, extra cheese.”

She gives me a devil’s laugh and she stands and goes to the service window. She takes the pizza to the Sig table and on her way back she stops near me.

“Don’t be afraid to ask.” She locks it in with her eyes and punctuates it with a quick nod and a smile.

She goes into the kitchen and before she can join her daughters at the service window, I leave.

The fuck?

The Crazy One in the Car is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely co-incidental.