Sophomore Year — Fall Quarter 1965

September 2, 1965

I know what’s wrong with me—besides being an overly-sensitive artist type. I don’t have dreams about boys for nothing. But why can’t I say that the way I feel about it is good and clean? And Jerry—oh, God—Jerry. All the things I’ve done and felt for him and still I try to talk myself into believing it’s just a normal, simple friendship?

Come on, Dave, you’re too intelligent to ignore facts—or to believe the way you’re distorting them. I can’t change the good feeling I have about liking Jerry. How can I feel that way and still detest the idea of a sexual connection? I like him; I hate homosexuality. How do I become a good friend, a person who cares and is concerned, without also feeling abnormal and unnatural? I want to be normal. But I don’t want to lose the real affection that has developed between me and Jerry.

And where does Carolyn fit in? Where do the sexual times with her come into play? Or were they just sexual because I was physically stimulated and couldn’t help feeling sexual—Admit it, Downs. Admit it.

*****

I’m at Carolyn’s house. It’s almost 3:00 a.m. Her parents came home a couple of hours ago and went upstairs. We’re lying on the floor in front of the sofa. Our feet have played together. Our knees have intertwined a bit. She puts her hand on my chest. I think she’s as hesitant to move her pelvis into mine as I am to hers. And I guess I’m relieved.

Her hands urge me closer as they knead against my back. I move my hand to her breast and she stops me, moves it down. I make a little protesting groan and she kind of laughs and kisses me a little harder. I’m wishing I would get an erection—or more of one because I think I almost have one. I turn toward the floor and push a little to keep it.

I love her. I love being with her. I want to be able to be carried away with her, to become with her. I wish I could say, “Help me. I’m scared.” I can’t. And, of course, if she touches my dick, I’d be paralyzed.

Her eyes look to my mouth, her finger touches my lips. She smiles and looks back up and I smile, too.

“What is this all about?” she asks gently. “What are we doing? Where are we going with this?”

Upstairs a door opens and someone walks down the hall. A light comes on. We know what that means.

“You’re glad,” she says not completely unkindly and I try for humor. “Whew!”

I put my shoes on and at the door we kiss.

September 13, 1965

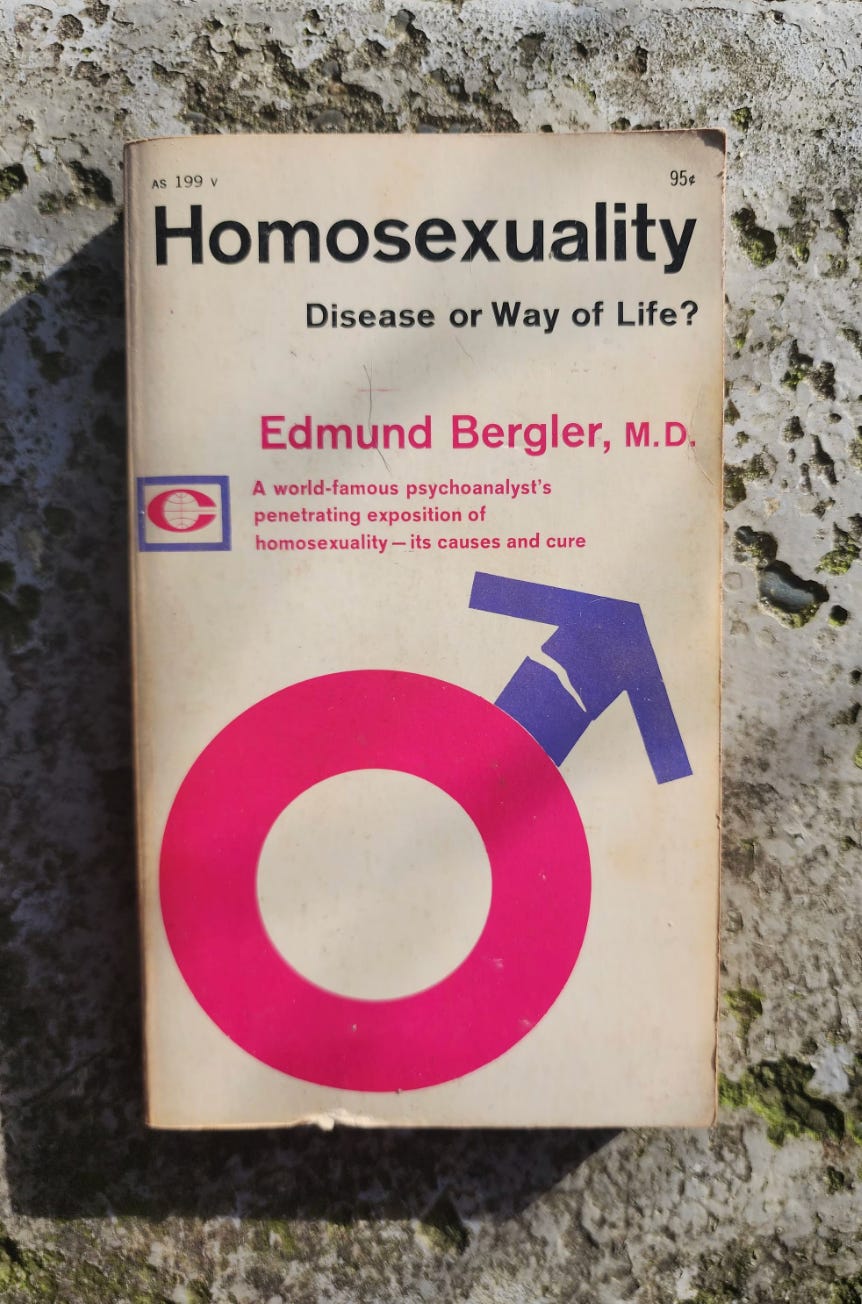

I read a book today—Homosexuality: Disease or Way of Life?—by Dr. Edmund Bergler. It denounces the idea of maternal dominance and paternal passiveness as the reason for homosexuality. Psychic-masochism is what he refers to as his reason. And from what he says, I think I might be leaning a bit in that direction. Still, the homosexual of Bergler doesn’t seem like me.

September 17, 1965

Upstairs on his bed Jerry and I wrestled. And we stopped, arms around each other. We kissed, we employed intercrural movement (as Dr. Bergler says) but most of all we held each other, we held on and loved the feeling that there was someone to hold and to hold you in return. I woke up with such longing—and seeing Jerry in his bed and me in mine made me know it wasn’t real.

Of course, I’m in Latrobe and Jerry is not in the room with me. Even in my dreams, if I’m with Jerry, it’s dreaming within dreaming.

Tomorrow back to Allegheny. It’s going to be the best year of my life. It’s going to be filled with good, strong, wholesome relationships. And I’ll be finding out once and for all time exactly what, if anything, there is to worry about.

*****

It’s Orientation Week and my schedule is full. As sophomore class president, I meet the freshmen and their parents and I lead groups on campus tours. There are official events each day and there are spontaneous gatherings. I’ve seen John Fergus’s apartment—Moth is his roommate—and at the house I’ve moved my stuff into the desk and the dresser in the upstairs study room. Jerry and I have the bunk beds in the far corner of the warm sleeping room. “Your legs are longer,” he said last spring, “so you take the upper one.” It feels a bit apart from the other bunks and I’m glad. I put my sheets on today and I keep looking at the empty mattress on the bunk below. He gets in tomorrow.

On the way to an Orientation planning session, I go by South Hall. Claudia is sitting at the fountain with several freshmen girls. I click into gear.

“Do you girls know how lucky you are to be sitting here with Claudia Vanco?”

They laugh. Alan Foster appears as if from the spray of the fountain. He’s a Sig and vice-president of the sophomore class and he thinks himself a galvanic force in the hearts of all women.

“Frosh,” he says as he smiles his big wide obvious smile showing lots of big white obvious teeth, “how many gallons of water are in this fountain?”

Two of the girls giggle as if they feel his galvanizing force and the littlest, blondest one with the hugest, bluest eyes, says, “Is that in the freshmen handbook?”

Alan acknowledges me with a nod. “Are the stockades going up today?” he asks. “We may have our first prisoners.”

Before I can answer, a clear voice from behind us says, “How many gallons of water are in the fountain?”

We turn and a freshman woman sitting between two freshmen men on the low brick wall of the patio tilts her head in mocking, wide-eyed innocence.

Alan laughs a bit gruffly and says, “David, sorry to leave you hanging, but we’ve got a meeting,” and off he goes.

Claudia says, “David, this is Molly Doherty.”

Molly stands from the soles of her feet right through her spine and up to eyes that glitter a bit as she reaches her hand to shake mine. “Well?” she says. Her eyes are blue and the lashes are short. Her almost red hair falls in straight bangs onto her forehead and along either side of her face to her jawline. “I’m betting even the grounds and maintenance men don’t know the answer.” She grips my hand and her ribcage lifts beneath the white blouse and her plaid skirt swishes as if on its own.

“Molly Doherty,” I say, “you are dangerous.”

Her eyebrows lift and her eyes go wide. “And David Downs, you like danger.”

There’s a burst of laughter from the other side of the patio and five freshmen men come over to us. Their leader says, “David Downs, right?”

“Right.”

“Question.”

“Yes.”

“Is your watch waterproof?”

Before I can bolt, they surround me and I am tossed into the fountain. I pull myself up to standing and freshmen come out of the South Hall doors, the girls applauding, the men cheering. “Dave Drowns! Dave Drowns! Dave Drowns!” One of the guys who tossed me in reaches his hand toward me and pulls me out. “Instant sophomore class president,” he says, “just add water.” Laughter and applause and cheers.

I look for Molly. She’s gone.

The next day it isn’t until I’m with Alan Foster in the Reis Library study room during the President’s Tea that I see Jerry. We’re with a group of freshmen and faculty and parents and he and Dan Corse come up the stairs. When I see him, he beams. I want to run over to him and pick him up and hug him and maybe even spin him around. But when they get to me, I surprise myself with my coldness. “When did you get in?”

This hurts him. “A while ago.”

“He dragged me over here,” Dan says.

“Where’s May?” I ask.

He looks directly at me. “She’s got Orientation stuff to deal with.”

“Oh yes”—with exaggerated realization—“that’s right, she’s on the Orientation Week committee and so she must serve.” Why am I doing this?

I see Molly coming up the stairs behind them. She walks over to us and her blue plaid skirt swishes. “Is this the receiving line?” she asks.

Jerry says, “I’ll see you later,” and he’s gone.

Dan says hello to Molly and then to me, “Oh yeah, did you know Ed Brown isn’t coming back?” and as he turns, “and Paul Felder transferred.”

“What?”

“Ed dropped out and Paul’s moved on.” And he leaves.

“How much longer do I have to wait till this event is over?” Molly says.

I want to go after Dan but I won’t give him the satisfaction. I’m abrupt with Molly. “Why?”

She ignores my abruptness. “You and I have to get some autumn leaves so I can make a talismanic wreathe for my door.”

“Ah. Well, I have responsibilities, you know.”

“To freshmen. I’m a freshman. Come with me. This couldn’t be duller anyway. Now.”

Alan Foster has been watching, so I tell him I’m leaving and he smiles his big smile and Molly and I go down the stairs and along the path to the ravine. We stop at a tall maple tree on the lawn behind Bentley Hall. Carefully she chooses a handful of leaves, some green, some yellow, and turns to me. “Let’s see what you’ve got.” I show her my leaves. Mostly yellow. Some brown. She moves them aside and touches the palm of my hand with her fingertips. “Under this tree,” she says, “is where you kiss me,” and she steps in to me and looks up. “And now is when.” And so I lean in to her and we kiss. She looks at me and I smile and we kiss again. It isn’t real.

At the house, I find Jerry in the study room. He’s sitting at his desk, his back to the door. “You left before I could tell you how glad I was to see you.”

He doesn’t turn around. “You were busy.”

“Can we talk?”

“I’m reading.”

I want to punch him.

At the end of spring quarter he came into my room and I threw my arms around him and said, “Good-bye, Jerry Caro,” and he reciprocated, he held me tight. ECB appeared in the door and I broke loose from Jerry and gave ECB an elaborate goodby hug.

Jerry turned away. “This kid’s going to pack,” and out he went.

After ECB left, I went to Jerry’s room. He was putting clothes in a suitcase.

I stayed in the doorway. “Well, I guess I’ll have to wait three more months for another chance at your bod.”

He kept his attention on the shirt he was placing in the suitcase. “Yeah.”

Some more garbage from me and, “Well….”

“Yeah, maybe you’d better go.”

I went. All summer I wanted to apologize. To explain. I want to be direct, open, straightforward with him. Why can’t I?

I got a job as a playground instructor with the Unity Township Recreation Board and I was assigned to Marguerite, a coal mining “patch” like Whitney in the country off Route 30. There’s not much for kids to do. As with most of the area mining towns, there’s a baseball diamond. Boys to the age of sixteen are allowed to play in the Summer Recreation Baseball League. I was the playground and Baseball League supervisor. At first I hated it: a four-year old girl calling people on the playground “doorty fuckoorhs,” kids smoking, adults slapping children. It reminded me of Whitney and the things I hate about my childhood.

But there was Joe Rozek and his friend Ron Hrusda. Joe and Ron were sixteen. Joe was short and dark and Ron was tall and fair. Joe and Ron liked me and I liked them. After playground hours I went swimming with them at a real live swimmin’ hole and they waited to see if I’d go skinny dipping with them. And I did.

Joe’s family liked me. One day I was sitting on the front steps of their house with Joe’s sister Audrey, who was studying psychology and nursing at Westmoreland Community College. I told her my mother wanted to know why I was spending so much time with the kids from Marguerite and I said it was hard to explain to her that I was making up for all the time I didn’t go to the baseball diamond in Whitney when I was little because I would rather sit on the front porch and draw. Once when my brother was going to the diamond with friends, Mom said, “Take Dave with you, maybe he’ll play if you take him.” I didn’t want to go but I didn’t argue. And I took my drawing pad with me. The next time Mom asked John to take me, he said he wouldn’t. “The last time, all he did was sit under a tree and draw.”

Audrey said she thought I was indeed trying to capture a part of childhood I had missed. It was a relief to hear her say that, but there was something else and I knew it. And I was hoping she would sense it and say it was nothing to be concerned about. No matter how much time I spent with Joe and Ron, I didn’t stop thinking about Jerry, and I knew there was a connection—especially with Joe. And by the end of summer, my affection for Joe was strong enough to make me want the playground to end. And when it did, I fought the urge to drive to Marguerite and I wanted school to start. I wanted to get back to Allegheny, to the house. To Jerry.

Now behind me in the hall Jerry says, “I need a break anyway.” I want to lean into him, to touch him as we come down the stairs. We’re in the narrow back hall when the swinging door to the dining room bangs open and Cragg and Graize burst through, locked in a wrestling hold and slamming against the wall. I duck into the doorway to the basement and Jerry pushes in against me. We go down the stairs and the banging continues in the upstairs hallway. Some light comes through two narrow windows at ceiling height.

I lift myself onto the ping pong table; my feet don’t touch the floor. He comes between my knees and puts his hands on my thighs—I won’t let him see me respond. “You’re going to be busy all week,” he says.

“Well, as sophomore class president, you know, I have enormous responsibilities in the shepherding of freshmen through a successful Orientation Week.”

He leans in toward me and then pushes away and then leans back in. “Lucky for you Molly Doherty’s a freshman.” Pushes away, comes back in. “No time for friends.”

I don’t move but my voice has weakened. “Always time for some friends. Always time for one friend.”

He smiles, pushes himself out and turns and leans against the table next to me. “I meant to write more often this summer,” he says. He’s looking at the floor. “But something always came up. Lame, I know.”

I could have written to him every day. We’re silent as we listen to the upstairs rumble.

“I hate myself sometimes,” he says.

Hope hits my heart.

“For procrastinating so much.”

Oh.

“I do it with May. I did it with Sue.” And he starts talking about Sue, about the other girls he dated in high school. He turns, puts his hands on the table top, pulses as he pushes back and then lets himself fall forward. “I had such a puritanical upbringing,” he says. “I think Mama would rather have a world where sex isn’t necessary.”

I want to protect the little private cocoon we’ve created down here. “I’m not sure my mother has ever actually seen my father naked,” I say. “Sex only after the lights were out. Jane said that one of Mom’s older sisters told her once, ‘You just lay there like a dish rag letting him do what he has to do and you hope it doesn’t take long.’”

“Mama has never gone on even one date since my father died.” Another push-off from the table. “I never did much. Physically. Even with Sue. It was so hard to try anything. And when I finally did, it seemed kind of dirty, like I was only doing it for her.”

Is this an opening? “When Carolyn and I are alone, she gets so worked up it’s like I’m cheating her because I feel so little—like I’m only doing it for her.”

He stops pulsing, pushes away from the table. “Well, that wasn’t my problem.”

The door bangs open and someone calls from the top of the stairs, “Downs! Rag! Get up here! Major wrestling match in the living room!”

“Well,” he says, and he goes up the stairs.

I sit in the downstairs silence a bit before going upstairs to join the fun.

The Crazy One in the Car is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely co-incidental.