Freshman Year — Fall Quarter and Christmas Break 1964

“Mama called today,” Jerry says. “My sister and her husband are coming from Colorado to spend the holidays at our house.”

Aha. We’re walking from the library back to Baldwin.

“And that means her brother will spend the whole holiday there, too, yes?”

He’s watching where his feet go on the pavement. “Yeah, I guess.”

I choose levity. “Jesus, man, that means you have to live for…let me count..uh…twenty-three days without seeing me!”

“Pretty much.” Still not looking at me.

“Pretty fucking heartless of your sister and her husband and—uh—”

He smiles. “Her Mama and her Gramma and Gramps Battaglia. They moved in with Mama and me this past summer, so….”

“Yikes.” And without thinking: “Where’s your dad? Where’s papa Caraggino?”

“He’s dead.” He still hasn’t looked at me. We pass the old stone bench that was a gift of the class of 1904.

“Oh.”

“When I was ten.”

I want to ask how and why but I don’t.

We walk in silence the rest of the way.

*****

ECBIV leaves for Christmas break without letting anyone know. Before Corse leaves, he tells me he hopes Carolyn and I get laid a lot. And Jerry catches his ride home while I’m taking my French II exam. A senior Crow I don’t know well but who lives in Pittsburgh offers to drive me to Latrobe and I accept. It’s a pleasant enough ninety-minute drive. He likes to talk and as a senior he likes to give advice and I smile and I look eager and responsive. Near the end of the drive, when we turn off the highway and onto Mission Road, I feel my stomach tighten. We come to Lawson Heights where less than a decade ago tiny brick California ranch-style houses transformed a one-and-a-half-square-mile chicken farm outside Latrobe into a 1950s housing development. There’s a thin layer of snow on everything and I’m glad. The sky is overcast and I’m glad. Edges are taken off, colors are grayed out. He’s telling me not to worry about fraternity pledging and we turn onto Loretta Street and I feel a little ball of panic growing in my guts and my smile becomes even faker, the “uh huhs” and the punctuating laughs of agreement even hollower.

“It’s the next driveway.”

As the car pulls up, Mom appears in the front doorway glad that the cold gives her an excuse not to come out to meet us. I get out of the car, take my suitcase from the back seat, thank him and he backs out and drives away. Mom opens the door and she imitates her Polish mother as I step in: “Yoi, yoi, yoi, Marush”—something she called me when I was a child, the meaning of which I still don’t know—“the college student is home.” She’s wearing a brown skirt I recognize and the blouse with brown and green and tan stripes that goes with it (We call that particular shade of brown “Repko brown” as she and her six sisters—maiden name “Rzepa” Anglicized to “Repko”—tend to choose clothes colored this nondescript brown or its gray twin). Her hair has a couple of bobby pins in it.

As I hug her, I see Dad standing behind her, smiling the awkward smile he gets when he’s about to crack a joke. His arms hang not exactly relaxed nor are they quite lifted and his hands, too, hang, the fingers not closed and not quite open. He puffs out a shallow breath.

“Hunh. Surprised your friend didn’t drop you off at Mission Inn and let you jog the rest of the way. Get you in shape for track.”

Mom says nothing, but I can hear her thinking hard as she takes my suitcase and goes toward the bedroom. I decide to deflect with mild humor. “He tried it, but I’m probably not going out for track, so he didn’t push it. I can take the suitcase, Mom.” I follow her into the bedroom.

“Gives ‘er something to do,” Dad says. “She’s been pacing around here the last hour like she’s waiting for the Pope.” He follows us. “When they find out about your hurdle record, they’re gonna be after you.”

It’s a small house. Under eight hundred square feet. The living room is a tiny rectangle at one end of which is the entryway to the tiny kitchen, at the other end of which is the entry to three tiny bedrooms and a tiny bathroom. In the years that John and Jane and I grew into the sizes of our parents, we found ourselves stepping over one another and making way for one another and in John’s case staying away as much as possible. The bedroom John and I slept in the past nine years still has the two knotty pine single beds. Mom nearly throws the suitcase on my bed and pushes past Dad as he stands in the doorway.

“Do you want something to eat?” she says.

Dad turns toward her and referring to me says, “This one’s always hungry. You better be stocked up.”

I decide not to try to call to her past him. He pads in short steps toward the dresser.

“Let’s see if she made room for you in here.”

My heart is beating fast. Guts are knotting up, chest constricting.

“I can keep it all in the suitcase.”

The next day he works the daylight shift at the mill. He’ll be gone till late afternoon. Jane and I are sitting at the formica table in the kitchen. Behind Jane Mom stands in front of the electric range frying more onions in butter.

“I haven’t made this many pierogi in a long time.”

I love the smell.

“Hey, Mum,” Jane says, “turn the stove off. Sit down for a minute.”

We’ve been talking about Dad.

“He looks better than he did when I left,” I say. “He’s gained weight. At least he looks alive.”

Mom puts a pot holder on the table and a pot of coffee on the holder. “The day we buried Uncle Joe, Jack Downs stopped smoking. Poor Joe. Three heart attacks in one day. On the way home from the funeral, Jack threw his cigarette out the window and he hasn’t had another one since. Over six weeks. You drink coffee now, right? You want milk and sugar?”

“Hey, Mum,” Jane says, “sit down a minute.” She picks up the coffee pot and pours into my cup. Her nails are longish and polished. A thin gold-link bracelet hangs on her right wrist. Her hair is combed back from her face and she’s wearing light make-up. The soft reds of her lipstick and her clingy sweater match. When we were kids in Whitney patch, she wore hand-me-down jeans and over-sized cowboy boots from our cousin Ray. She hated having her hair washed and she was tough; she was my constant companion, my defender.

She looks at me looking at her. “What?” she says.

“I was remembering the day Bobby Lesko asked you how big your prick was.”

“And I said it was bigger than his.”

Mom bites her lower lip and puts her hands over her ears. “You two,” she says.

*****

Dad blusters about trying to be helpful. To be needed. He’s gained weight but his pants still hang on him. His chest has slipped—he looks like a cartoon fairy tale witch with a slightly deflated basketball belly. His eyes still bulge but there is no longer ferocity behind the bulge. He follows me around the house trying to find things to say, ways to help. Trying to find a way in. He wants to skip over the part where he apologizes for past brutalities and we talk and talk and end up crying in each other’s arms. He’s trying to skip over that and land us in the middle of the relationship where we trust each other and love each other and welcome each other into our lives and and and. But I can’t. I won’t. I can’t react confrontationally—Jane can do that and get away with it. I don’t absent myself physically—John’s M.O. for all his teen years. And now John’s married and Mom says she thinks he fell in love with Carol Pevarnik’s dad as much as he did with Carol. And so I close off. I shut down.

It used to take enormous energy for me to be unresponsive to him. When I was alone, I would shake, cry; during sophomore year, my hair fell out in patches. He no longer sets off rage within me but neither is there pity. I look at him as if I were watching a National Geographic documentary about an unusual species of something or other. It exists but it doesn’t affect me. Mom says I’m to blame for the tension in the house. “Tell him what you think. Stop holding it in. Maybe he’ll leave you alone.” But I can’t. He keeps trying to engage me, but I will not engage. He’s solicitous, even a bit fawning, and the Twilight-Zoney part is he treats me like a mentally challenged five-year old.

It’s late afternoon. I’m sitting on my bed polishing my loafers—an excuse to stay in my room. The door pops open and I jump a bit in panic. No one in this house has ever knocked on a door before entering. Dad pokes his head in. Part of me wishes I was standing here with my pants around my ankles, dick in hand. He’s smiling conspiratorially and he practically tip toes in and closes the door behind him looking like a homeless Santa with a secret.

“Hey Davie”—he’s called me that a few times this week—“Mommy’s making fudge”—did he just say Mommy?—“you know, like she always does? And I asked her if you’d like to lick the bowl. She said no, but I remember when I was little”—Jesus Christ—“how I used to like to clean out the bowl when my mother made something. Me and your Aunt Rita used to fight over it.” He looks at me expectantly.

I want to say something cruel, but I can’t; I want to go along with this grotesquerie, but I can’t. I want to stare at him and say nothing, but I can’t.

Tonelessly I say, “Who won?”

He blinks.

“Oh, fifty-fifty,” and he turns and leaves.

He calls me “Captain” now, too.

*****

Jane has a date tonight. I can hear her moving about in her room, going from the bathroom—water turned on, the mirror of the medicine cabinet opened, closed, the door opened—back to her room. Door closed. Dad’s sitting in the living room waiting for something to happen. Mom is in the kitchen. I can hear her washing dinner dishes. Jane comes into the living room. Her hair is brushed back and falling easily to her neck. Light make-up. She’s wearing a gray crew-neck sweater and black skirt, flats. I think she told me that her date is shorter than she is. She stops in front of the television to clip the gold chain-link bracelet onto her wrist. Dad shifts in his chair as if he’s about to say something and she anticipates him.

“Here’s the plan,” she says. “I don’t want any corny jokes. I don’t want you demonstrating your camera or showing him your pills. I’ll introduce him, you’ll say you’re glad to meet him, and then we’ll leave.”

I’m aware that all sound has stopped in the kitchen. Dad gets up and goes into the kitchen and down the stairs to the basement. Mom comes into the entryway. She looks surprised, sad. Her eyes are shiny.

When Jane comes back from her date, she and I sit in the kitchen and talk. Dad and Mom have gone to bed.

“I had a dream a couple of weeks ago,” she says. “I was running from him down narrow streets and I hid behind a building and when he came past I jumped out and stabbed and stabbed and stabbed. I woke up shaking and crying.”

*****

Best friend Howdy tells me friend Keith is home for winter break. I want to talk to Keith about Carolyn and ECBIV and Jerry. Last year he understood my fears about not being turned on by Carolyn. He said he was glad to know there was somebody who felt the way he had about Judy the year before. But I think my fear of that talk is stronger than—or rather, my fear of what I’d find myself saying is stronger than my wish to say it. I think if he wanted to he could permeate me—like one of those one-celled creatures from biology films that almost effortlessly breach the cell walls protecting other cells. Howdy is my best friend but Howdy cannot breach the cell wall. We engage each other. We share humor and intellect and artistry—he’s a music major at Carnegie Tech—but we don’t penetrate the other’s cell wall. Whatever that means. I think Keith could penetrate my cell wall. I don’t want to see Keith because I’m afraid to find out what that means.

*****

I’m at Carolyn’s house. Her parents are out for the evening. We’ve talked about her Allegheny visit and she’s asked about Claudia and John.

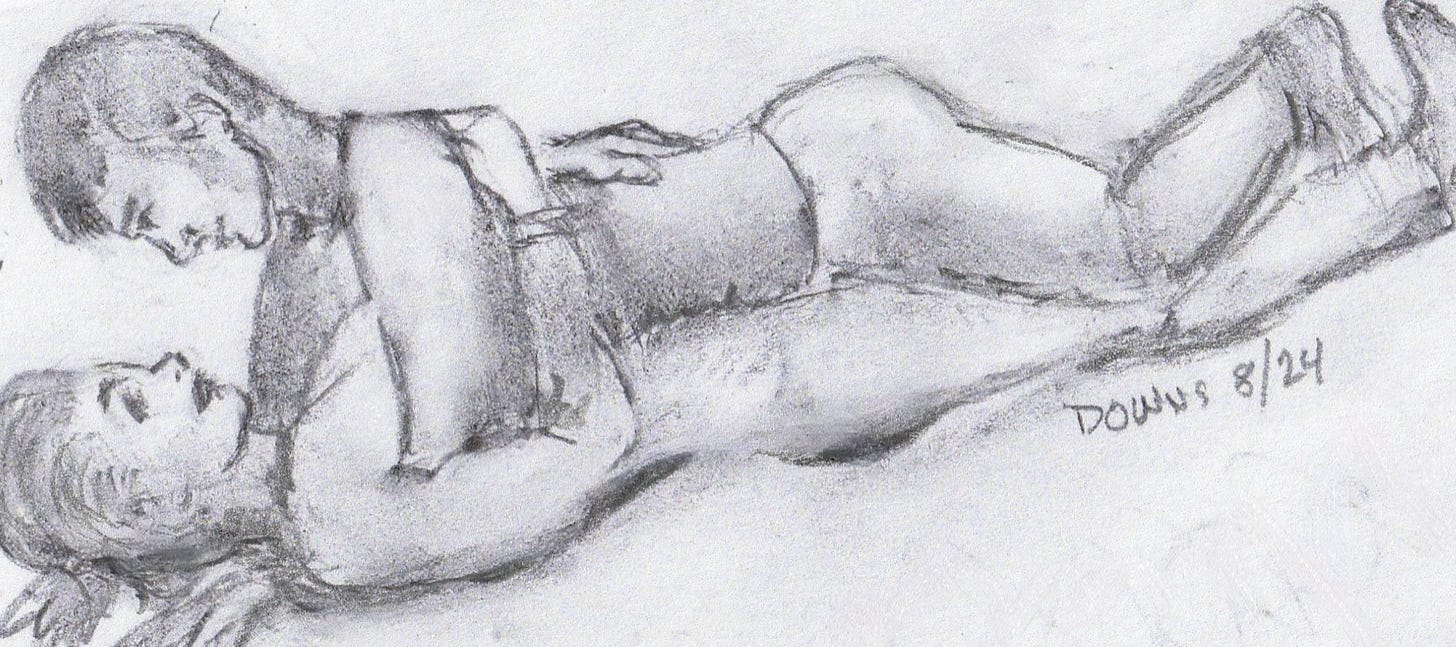

She puts a Johnny Mathis album on the stereo and she dims the lights and we lie in front of the fire. I love the smell of wood burning and the hiss and pop of sparks. She’s on her back, the leg near me bent at the knee, and I’m leaning on an elbow looking at her profile in the fluttering light.

Johnny sings Chances Are and she turns her head toward me and she smiles and lowers her leg. It feels like an invitation. I lift myself over her, look into her eyes. Does she want me to move on top of her? I lean toward her and we kiss. It’s a long, easy kiss, but I’m beginning to panic. I’m not getting hard. I’m not going to get hard. A couple of gentle kisses and I lift up and slowly roll off.

“What’s the matter?” It’s gentle, it’s caring.

Inside me something wants to find its voice. I’m trying to speak for it, to interpret. “I don’t know, I…I’m not sure.”

She faces me, watches me.

“I guess I just hate it here.”

“Jesus.”

“Here Latrobe, I mean. I want to get back to Allegheny.”

She rolls onto her back.

I have to try to find the words. “I don’t know…what it is—or why—not sure what’s going on, but I think I don’t want to feel…obligated—I don’t want to have to be careful about other people’s—”

“Do you think of me as an obligation—”

“No!”

“—while you’re hating everyone and everything else?”

“No. This is all outside of you. It’s about my family, I guess, mostly. You’re the thing that saves it.”

She sits up, looking into the fire. Her voice is calm. “Am I just somebody to write letters to, to have fun with on vacations?”

This was not spontaneous. This is something she’s been thinking about.

“No.” It comes out weaker than the other ‘nos’ have been.

She goes to the Christmas tree and gets a small holiday-wrapped package. She hands it to me, smiling her resigned, understanding smile. “Merry Christmas.”

“I’m sorry I can’t explain—it’s hard for me to understand, to—”

A car door slams in the driveway.

“Christ,” she says. Wiping her eyes with the back of her wrist, she goes to the dimmer switch and brings up the living room lights.

The front door opens and Mrs. Crawford’s laughter fills the hall. She’s taking off her coat as she comes into the entranceway.

“Carolyn, we’re home early, a party at the Thompsons’ is as dull as are the Thompsons, and you two should be out somewhere having fun.”

Behind Mrs. Crawford is a couple I have met but whose names I can’t remember. And behind them Mr. Crawford comes in and takes their coats.

Mrs. Crawford says, “Grant, Nancy, you know David Downs, I think.”

I step forward and shake Mr. Swatcher’s hand and Mrs. Crawford turns me around sharply. “Well, now, Carolyn, perhaps we shouldn’t trust the two of you to be alone,” she says as she tugs at my exposed shirt tail.

Mrs. Swatcher laughs and Mr. Swatcher says, “You’ve been found out, David, she’s relentless.”

Mr. Crawford goes to the bar and makes drinks. Carolyn manages a “Mother” somewhere between anger and anguish and she gets my jacket and goes out with me to my car.

“I hate her,” she says.

In the car home I’m thinking: I’m on a long-playing record and the needle’s stuck. And I’m holding her there with me. I want to find my way back to normal. To feeling and being normal. But what about ECBIV and Jerry? Are my feelings for them normal? And the fraternity. If I’m not normal, what will happen with the fraternity?

I’m sitting in the car in our driveway. I unwrap Carolyn’s present. It’s two books: Winnie-the-Pooh and Alice’s Adventures Underground. There’s a card: “To David, who says he was never read to as a child. These are yours to keep. The love that goes with them is yours for as long as you want it. Carolyn.”

When I open the front door, Dad’s standing there holding something behind his back. He’s trying to look mischievous but his face doesn’t know how to do that.

“Guess what came in the mail today.”

“Don’t make me guess.”

He hands me two envelopes. A Christmas card from Jerry and something official from Allegheny College. My grades. I open it. English I, A; French II, A; Drama I, A.

Dad goes into the kitchen. “Well, he’s doing something right. He got all As.”

I open Jerry’s card. “Christmas Greetings 1964! I should have known I’d send cards. Especially to you, Dave. I really miss you. And everyone. Can’t wait to get back. Try to stay merry til then. Jerry.”

December 31, 1964

I’m sure—well, pretty sure—that the Fourth-of-July-Fireworks type of love is fictional. That what I feel for Carolyn is normal and genuine.

But I don’t want her spending her whole life with me. It wouldn’t be fair to her. I think I’d be a miserable husband.

And there’s the possibility of abnormalcy. All right, I’ll say it—homosexuality. Latent or just unadmitted. It’s hell to think about. Though more and more I’m convincing myself that I’m not homosexual—that I have normal feelings and a huge anxiety imagination.

To write. To teach. To act. At year’s end I still would love to do all three.

I can’t wait to get back to Allegheny.

The Crazy One in the Car is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely co-incidental.

My heart hurts.